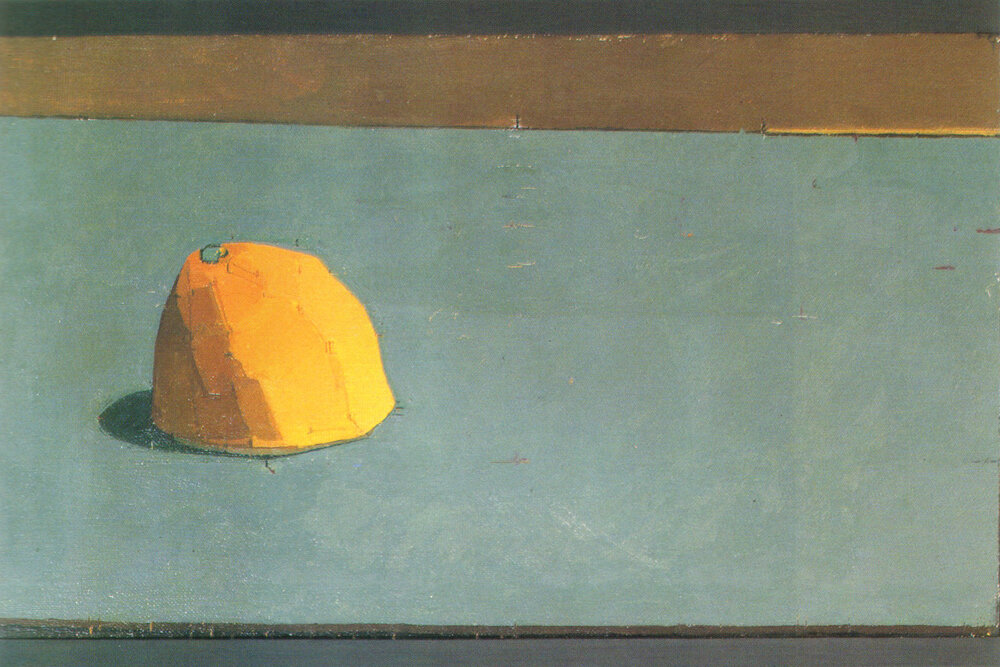

Lemon, 1973

Oil on Canvas, 19 x 33cm

Private Collection, Not Seen

In July 2003 I went to see the first public exhibition of the work of Euan Uglow since his death from cancer in 2000. Disappointingly this painting of half a lemon was not included in the show. It is quite unsual in that most of his work whether of nude models or still life involved a dynamic pose. The artist notoriously placed his models in geometrical and sometimes stiffly contorted poses and since he sometimes took up to five years to finish a painting and only ever painted from life, his models had to keep such poses for considerable lengths of time.

There is a sense of harmony within the image, not just about the placement of the lemon on the grey shelf, but also the weight of the graduated yellow in relation to the size of the background. The lemon is strongly lit from the right and his planes of colour give a suprising degree of three dimensionality to the flat surface.

I have seen a lot of Uglow’s paintings and drawings and this looks typical of his method working. Taught by William Coldstream at the Slade School of Art in London, he used little registration points and tiny painted crosses to help the drawing process. It is worth noting that his obsession with accuracy ran to marking these reference points on the skin of his life models and that they had to keep these marks between sessions. These marks always remain in the finished painting, revealing the history of its making by a prolonged process of looking hard.

He sometimes took up to five years to finish a painting and only ever painted from life and the marks become a record of the temporal aspect of painting. This recording the passage of time is taken a step further in a little painting I saw in his exhibition at the Holburne Museum of Art, Bath called Diary of a Pear, 1972. He placed the tip of a pear at the exact centre of a perfect square, but he painted so slowly that the pear rotted, and the tip drooped. So each day he began a new square with a new centre point and a series of marks showing where the tip had once been. He has said in interview that he “isn’t interested in producing pictures; but in personal research”

Perhaps because of this perfectionism his paintings seem to lack emotion and whilst I find them technically interesting I don’t feel that they have a melancholic aura, even when the subject is a lonely half a lemon.

©blackdog 2020